Training the Pumi

Introduction

How should we begin?

How should we begin?

I’ll review a feasible training method for several common basic tasks, without the claim for completeness– after all, in real life countless unique situations can occur, which need to be drilled into the dog. I don’t want to touch upon these right now.

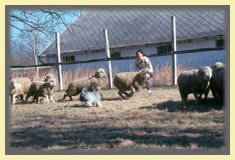

Nearly any situation can be resolved by mastering the basic tasks and with a little creativity. I have to emphasize an important point regarding training: the dog, especially if it’s still a puppy should be only taken to an expert for training, because bad advice and incorrect methods can ruin the dog – and the owner - for life. For Pumi training preferably a dog/people-broke cohesive herd of 30 – 50 sheep of a not too nervous breed would be ideal in the beginning.

The commands mentioned here are only suggestions – any word can be used for individual commands, but their sound must be clearly distinguishable, otherwise the dog will confuse them with each other.

The methods described here are only guidelines, because every dog has its own personality, reacts differently, may have different habits; therefore in many cases the method has to be tailored to the individual dog.

It is strongly recommended for herding training that the dog should already possess basic obedience and excellent relationship with the owner, i.e. it can be recalled with a high degree of reliability and can stay in place. The dog has to respect its owner under any and all circumstances – not only at home, but around sheep as well. This shouldn’t be a problem in the case of proper dog-owner relationship. This stable foundation is absolutely necessary for building the herding work on it. Until this is established, we shouldn’t even attempt herding. This foundation can be taught and practiced in other venues, not only with sheep, but for example while walking the dog, or in any other situation where the dog is exposed to strong external stimulation.

It is strongly recommended for herding training that the dog should already possess basic obedience and excellent relationship with the owner, i.e. it can be recalled with a high degree of reliability and can stay in place. The dog has to respect its owner under any and all circumstances – not only at home, but around sheep as well. This shouldn’t be a problem in the case of proper dog-owner relationship. This stable foundation is absolutely necessary for building the herding work on it. Until this is established, we shouldn’t even attempt herding. This foundation can be taught and practiced in other venues, not only with sheep, but for example while walking the dog, or in any other situation where the dog is exposed to strong external stimulation.

In the course of instruction, we should use gestures in addition to consistent verbal commands to make the dog understand what we’re expecting of it. The dog mainly understands body language and pointing gestures; later it’ll associate verbal commands with these gestures.

The verbal command can be anything, even “ketchup” or “thistle”; the important thing is to use the same word for the same action. This way the dog will be able to associate the sounds with the gestures. If later on it hears a word, it’ll execute the command which is stored in its memory associated with a task. It’s important to remember that the dog doesn’t understand our language, but remembers words by their sound; that’s why commands should have distinctly different sounds so the dog can unequivocally decide what we want from it, even from a distance. In this case handclapping and whistle signals work very well. For example, one short or two long blows with the whistle can be heard very well at a distance, and the signals can be easily distinguished from each other. Hand signals can be used as well, however if there is an object or terrain feature between the dog and the handler and the dog can’t see the hand signals, some sort of sound signal is necessary. For working beyond hearing and visual range the dog’s extensive experience and mutual trust with the handler is indispensible.

Dogs have a strong drive for a structured behavior - just like we do; the essence of which is striving for cooperation. That’s why it’s not enough to expect that just by using verbal commands the poor dog will figure out what we want from it, we need to give it a cue by using gestures. This is the learning phase. If the dog understood what we want from it, we need to practice so it’ll be ingrained – this is the fixating phase. Praising shouldn’t be skipped after each well executed command! The training should be built on positive reinforcement rather than chiding for mistakes. In other words, if the dog makes a mistake, we don’t scold it, but we immediately stop or recall it and repeat the command. If it completes the entire task, praises should follow. While working with sheep, rewards such as a ball, favorite toy, food treat can’t be used, therefore excellent dog-owner relationship is extremely important, where the dog’s reward is the owner’s joy and satisfaction, as well as the work itself!

Dogs have a strong drive for a structured behavior - just like we do; the essence of which is striving for cooperation. That’s why it’s not enough to expect that just by using verbal commands the poor dog will figure out what we want from it, we need to give it a cue by using gestures. This is the learning phase. If the dog understood what we want from it, we need to practice so it’ll be ingrained – this is the fixating phase. Praising shouldn’t be skipped after each well executed command! The training should be built on positive reinforcement rather than chiding for mistakes. In other words, if the dog makes a mistake, we don’t scold it, but we immediately stop or recall it and repeat the command. If it completes the entire task, praises should follow. While working with sheep, rewards such as a ball, favorite toy, food treat can’t be used, therefore excellent dog-owner relationship is extremely important, where the dog’s reward is the owner’s joy and satisfaction, as well as the work itself!

What should we pay attention to while herding?

It’d be ideal is if we could familiarize our young Pumi with sheep from 6 months of age.

In the beginning we walk gently around a small, calm dog-broke herd (30-50 sheep). If the puppy is not interested in the sheep, or is afraid of them, we shouldn’t force the issue and we should try again in a month.

The puppy would alertly watch the sheep, but still keeps its distance from them. It happens often that it’ll hide behind the owner’s legs and will curiously peek out from there.  We believe that as long as it’s watching the sheep, there is nothing wrong; it’s almost sure that that dog will start as soon as it feels sufficiently self-confident. It pays to wait patiently until the dog gains enough self-confidence. It’s possible that it’ll be self-confident enough to dare to advance towards the sheep only when it’s one year old.

We believe that as long as it’s watching the sheep, there is nothing wrong; it’s almost sure that that dog will start as soon as it feels sufficiently self-confident. It pays to wait patiently until the dog gains enough self-confidence. It’s possible that it’ll be self-confident enough to dare to advance towards the sheep only when it’s one year old.

When the dog realizes that the livestock is really afraid of it, that’s all it needs to experiment with its strength as a game; it’ll repeatedly scare the sheep by stamping its front feet, maybe will also bark at them. The sheep will scamper away even more, and the process continues until the dog is completely encouraged and will run around the flock, barking. We consider this as the fully awakened herding instinct in the dog. Quite often another, experienced dog is necessary to “start up” the instinct. While the young dog is watching, we send out the experienced dog to the flock to circle it and bark at it, thereby to move the livestock a little. The stationary, grazing sheep are not as motivating to the puppy as moving animals. Sheep in motion will awaken its interest as it gains courage from the presence of the other dog, and will start experimenting.

In the beginning the young Pumi should be taken to the flock just to “play” and we should let it romp freely around the livestock. It should be left alone to enjoy this “work”, because later on it’ll be easier to make it work on hot days. The first few sessions shouldn’t be longer than 5 minutes each as young, inexperienced dogs tire fast from intense concentration. We have to be aware though, that dog broke sheep recognize the beginner, weak dog immediately, they won’t be afraid of it; on the contrary – they’ll have the tendency to lunge towards the dog, stamp with their hooves and in many cases to strike out with their horns. Some more hot-headed sheep could actually butt the unsuspecting young dog. We have to avoid this kind of situation by turning the sheep’s head away from the dog’s direction, because a successful charge by the sheep will cause the dog to lose interest for a long time or could develop a sense of fear towards livestock in the dog which will be a negative influence on further herding work.

In the beginning the young Pumi should be taken to the flock just to “play” and we should let it romp freely around the livestock. It should be left alone to enjoy this “work”, because later on it’ll be easier to make it work on hot days. The first few sessions shouldn’t be longer than 5 minutes each as young, inexperienced dogs tire fast from intense concentration. We have to be aware though, that dog broke sheep recognize the beginner, weak dog immediately, they won’t be afraid of it; on the contrary – they’ll have the tendency to lunge towards the dog, stamp with their hooves and in many cases to strike out with their horns. Some more hot-headed sheep could actually butt the unsuspecting young dog. We have to avoid this kind of situation by turning the sheep’s head away from the dog’s direction, because a successful charge by the sheep will cause the dog to lose interest for a long time or could develop a sense of fear towards livestock in the dog which will be a negative influence on further herding work.

If we can’t keep the dog at a safe distance, we should try to keep it close to us, so we could assist if a sheep should unexpectedly charge it, by stepping out and chasing the sheep back into the flock. One solution is getting into the midst of the flock or we could knock gently on the sheep’s horns or head with the shepherd’s staff which will make it turn back into the flock or to retreat; in either case it’ll give up its intentions.

In the midst of the free, playful chasing of sheep we have to pay attention to several things in the young dog. If it gets highly encouraged and consistently starts to grip the sheep, we have to stop it immediately. We shouldn’t scream at it, but it should be a rather hard, determined “stop!” and we should immediately send the dog back to signal that we have no problem with herding, but only with its action at that moment. After a few times of this, the dog will realize that the problem is with its gripping. We should take care of sending in the right direction from the beginning because the mistakes will get strongly ingrained even at this young age; but we shouldn’t expect the dog to perform any particular tasks.

If a sheep breaks away from the herd, the dog will start to chase it instinctively. Because of inexperience, in many cases the dog may place itself on the wrong side of the running sheep, so instead of helping it rejoin the herd, the dog chases it farther and farther away. After a while, experience will help the dog to always be on the opposite side of the sheep from the flock; this will enable it to turn the sheep back into the flock. Until the dog senses this, we shouldn’t let the dog chase the sheep wildly, so that this task won’t be ingrained incorrectly; therefore we have to stop the dog immediately or recall it until the sheep slowly returns to the flock.

If a sheep breaks away from the herd, the dog will start to chase it instinctively. Because of inexperience, in many cases the dog may place itself on the wrong side of the running sheep, so instead of helping it rejoin the herd, the dog chases it farther and farther away. After a while, experience will help the dog to always be on the opposite side of the sheep from the flock; this will enable it to turn the sheep back into the flock. Until the dog senses this, we shouldn’t let the dog chase the sheep wildly, so that this task won’t be ingrained incorrectly; therefore we have to stop the dog immediately or recall it until the sheep slowly returns to the flock.

We shouldn’t allow the dog to fight with a sheep which is charging it. With time the dog will learn that as long as it’s fighting, the sheep will not even think of returning to the flock, because this is how it’s protecting itself – that’s why the dog has to move away, rendering the sheep’s charge useless and thus it’ll escape back to the flock. If the dog stops to fight with the sheep, often the flock will walk away, out of the dog’s control while the dog is fighting and forgetting about everything else. Young dogs with really good instinct will “outmaneuver” the charging sheep by lightning fast back and forth movement; it’ll be incorrect to send such a dog later to bite the misbehaving sheep, because we’d be teaching it exactly what’s undesirable.

The dog does this “maneuvering” – turning the sheep more and more away from its attacking position, until the sheep gives up and will prefer to turn and run back to the flock. If our dog does something like this instead of fighting, let it continue, thereby reinforcing this excellent solution!

If our young dog definitely can’t cope with the sheep, we step in, and help it by moving the sheep with the staff, turning away the sheep by its head.

If our young dog definitely can’t cope with the sheep, we step in, and help it by moving the sheep with the staff, turning away the sheep by its head.

We should try to send the dog in direction from the beginning, but if it does this incorrectly, we shouldn’t chide it; we should recall the dog without praising it and resend it in the same direction. Alternately we could stop it and then resend it in the right direction. In the beginning there shouldn’t be a large distance between us and the sheep. If the dog performed well, we should praise it lavishly. To emphasize, if we let our dog run in the wrong direction many times in the beginning, or we allow it to get into a fight with a sheep, we unwillingly drill these things in the dog, before we even start any purposeful training. It’s harder to correct bad habits than to teach a new task.

If our dog already consistently runs in the correct direction and circles the sheep, we send it back and make it turn by swinging the arm or herding staff as we are stepping in front of the dog on the opposite side of the flock. A dog with good instinct will develop a gathering movement in a short time from this and it’ll be easy to keep it on the opposite side of the sheep from us.

When the dog visibly enjoys being with the sheep and has the required self-confidence, discipline, and can be reliably recalled, then we can start building our herding work step by step in the order described here.

These steps follow each other and are built on each other.

Basic exercises

Recalls, holding in place, stopping, sending in direction, keeping distance

The most important foundation of herding is that the dog should be disciplined and can be recalled immediately - and should obey its owner unconditionally. If someone who works with a dog is not strong enough to make decisions, the dog will decide for that person. All the subsequent series of tasks are built so that we can lead the dog to accomplish more complicated tasks independently, as well as to correct mistakes by stopping, recalling and by holding in place.

The most important foundation of herding is that the dog should be disciplined and can be recalled immediately - and should obey its owner unconditionally. If someone who works with a dog is not strong enough to make decisions, the dog will decide for that person. All the subsequent series of tasks are built so that we can lead the dog to accomplish more complicated tasks independently, as well as to correct mistakes by stopping, recalling and by holding in place.

If, for example we want to teach our dog to turn back in a timely fashion before it comes up to the front of the sheep, thereby stopping them – we can cue the dog to what we actually want, by stopping and recalling it. If the dog got used to not obeying the command immediately, the momentum will bring it right up to the sheep; we’ll have to yell the command 4 or 5 times before the dog obeys. By this time we’ll be pretty far from our goal.

We can easily recognize that this will make it much more difficult to get the dog to understand that we only want to change the flock’s direction and not to stop it.

We can practice recalls without sheep, for example in a park, while taking a walk and meeting acquaintances with dogs. We can practice the recall in the midst of the dogs playing with abandon, by calling our dog from time to time away from playing, and releasing it back to play after rewarding it. This situation is very much like being in the vicinity of sheep, because playing with another dog is almost as attractive to a dog as sheep. The important thing is to praise the dog after every successful recall; we should keep it with us for a little while and then release it to continue playing. If we don’t let it go back and continue, the dog will develop an instinctive resistance to the recall, as it learns that this is the end of playing and will never come willingly.

Staying in place is at least as important a requirement as the recall. It can be practiced in the same situations as the recall – in other words, when we recall our dog, we don’t let it go back immediately, but make it stay in place for a few seconds with the “Stay” command. If it was obedient, as a reward we release it back to its playmates. This will develop confidence in the dog, namely that recall and staying in place don’t necessarily mean a bad thing – the end of playing - but the dog also gets used to going back only when we send it and not when it wants to go.

Staying in place is at least as important a requirement as the recall. It can be practiced in the same situations as the recall – in other words, when we recall our dog, we don’t let it go back immediately, but make it stay in place for a few seconds with the “Stay” command. If it was obedient, as a reward we release it back to its playmates. This will develop confidence in the dog, namely that recall and staying in place don’t necessarily mean a bad thing – the end of playing - but the dog also gets used to going back only when we send it and not when it wants to go.

A more serious level of staying in place is when we command the dog to sit or lie down and we walk away from it. In the beginning we only go to 3 to 6 feet away and we continuously emphasize to the dog that it has to stay there. If it moves, we make the dog sit in the original place and we start from the beginning. If the stay works out to such a degree that we can turn our back to the dog, it means that the dog trusts us. We can then increase the distance. This way gradually we will achieve distances as far as a few hundred yards. A very important point is that the dog can only leave its place by command; this could be for example a recall. In many cases there is a need for stopping a dog and having it stay in place; practicing this exercise increases the dog’s self-confidence. This way the dog can be slowed down, and working with a perhaps more worried, less dog-broke flock it could be distinctly more useful if we can hold back our otherwise excitable dog – we can do more damage than good with volatile temperament in the vicinity of a nervous flock.

With slower, more sedate work the sheep won’t run away and won’t scatter as much.

In the video we can see a nice stopping of the flock by a beginner dog. The fence is helping the dog so that it prevents it from running around the sheep. Therefore the dog will stop on the command exactly where it’s supposed to: in front of the sheep. The fence is also practical for sending in direction, as it won’t allow the dog to cross over. Both practical elements are well ingrained in the dog.

(Video by: Takács Ferenc,

featuring Magyar Zsuzsanna and Vöröskői-Kondacsipkedő Gyopár "Rigolya")

When sending in direction, in the beginning we should stay close to the sheep, helping our dog as much as possible. If we’re closer to the seep, our dog senses better in which direction we’re moving relative to the flock, i.e. by swinging our arm; the dog won’t have the room and time to switch to the wrong direction because we can step in or point between the dog and the sheep with our staff to prevent the dog from starting out in the wrong direction. Later on we can gradually increase this distance.

When sending in direction, in the beginning we should stay close to the sheep, helping our dog as much as possible. If we’re closer to the seep, our dog senses better in which direction we’re moving relative to the flock, i.e. by swinging our arm; the dog won’t have the room and time to switch to the wrong direction because we can step in or point between the dog and the sheep with our staff to prevent the dog from starting out in the wrong direction. Later on we can gradually increase this distance.

We stop or sit the dog 15-18 feet from the sheep. We walk by the sheep and we send the dog in one direction with our chosen command, such as “come by”. When the dog starts out towards the sheep, we start walking towards the dog at the same time, pushing it away from the sheep. If the dog goes in a nice arc, we step back to our starting point and let the dog circle around. We always point with the arm in the direction we want to send the dog. In order to avoid confusion in the future, never cross these signals! It’s very important that the handler is connected with the sheep by an imaginary line. The dog can’t cross this line; it can go around the handler and the sheep, “outside”, without crossing it. This boundary line has to be strong enough so that as the handler moves, he/she practically pushes the dog “out”. This method is very useful for drilling in the “sending in direction”.

When the dog happily runs towards the sheep we let it entertain itself for a little while, then we call it back to us and reward it.

First we practice sending, recall and distance keeping very thoroughly. We should watch out that the dog always circles the flock from the side we sent it to. If it goes out in the wrong direction, we stop it immediately and we either send it in the correct direction again, or we recall it and send it again. We have to restart the exercise every time the dog starts out in the wrong direction.

Keeping distance is one of the toughest tasks for the Pumi. It’s only possible to work with a few sheep very calmly, that’s why teaching to keep a relatively larger distance is one of the most important things. The dog has to “feel the sheep”, to sense that if it’s farther away from the flock, the flock will act less nervously.

Keeping distance is one of the toughest tasks for the Pumi. It’s only possible to work with a few sheep very calmly, that’s why teaching to keep a relatively larger distance is one of the most important things. The dog has to “feel the sheep”, to sense that if it’s farther away from the flock, the flock will act less nervously.

In order to achieve this, and that the dog should learn to think about the flock as a whole and not about individual sheep, it’s better if we start teaching it to work calmly from a distance by using only a few sheep.

From this point on it’s really not a task for beginners because the dog and the owner have to cooperate very closely!

We form a flock with a few sheep in a 60-90 feet diameter small round pen and we send the dog around them so, that we push the dog continuously with our body, keeping it away from the sheep. The simplest way of doing this is to reach to the other side of the small flock with the staff, or we step out from the flock decisively towards the dog as if we wanted to rush at the dog and then we step back into the flock. At the same time we say the command “get back”.

This will come handy later in distance work, if the dog happens to intimidate the sheep. If the dog succeeds in tricking us, never chide it, instead we step in resolutely between the sheep and the dog, as if we were protecting the sheep; then we step back into the flock. The dog will instinctively distance itself from the sheep. (Don’t expect much from Pumik, 6-15 feet is considered a nice distance for them as the only way for them to exert enough influence on the much larger livestock is to be very close; this way they can also nip the sheep emphatically if it doesn’t move the way it’s supposed to. Pumik can’t influence the sheep with stalking, hunting movements and by staring at it; their “fighting style” dictates something else.) We send the dog in both directions several times around the sheep, until it learns to keep its distance from them. This way the directions will be drilled into the dog. Then we can step back a little, leaving a larger distance but always only as far as the dog is still reliably controllable. Do not neglect to praise and to reward! When all this is accomplished in a stable fashion, we can increase the number of sheep and continue the distance exercise until the dog learns to stay farther away from the sheep. This is beneficial for a number of reasons: the dog always sees us and we see the dog and it’s less likely to nip than if we let it work too close to the sheep. Furthermore, the directions – independently from us - would be perfectly drilled into the dog; stopping the dog can be also practiced as part of this exercise, because we can stop the dog at will while it’s circling around. In addition, a new command can be introduced here, “go on”, which we use to encourage the dog to continue the circling or to further advance. This also comes handy, for example we stop the dog to slow it down, and we need to start it again, we will be able to send it on its way again with the “go on” command. With all these combinations we’ll be able to perform precise work!

This will come handy later in distance work, if the dog happens to intimidate the sheep. If the dog succeeds in tricking us, never chide it, instead we step in resolutely between the sheep and the dog, as if we were protecting the sheep; then we step back into the flock. The dog will instinctively distance itself from the sheep. (Don’t expect much from Pumik, 6-15 feet is considered a nice distance for them as the only way for them to exert enough influence on the much larger livestock is to be very close; this way they can also nip the sheep emphatically if it doesn’t move the way it’s supposed to. Pumik can’t influence the sheep with stalking, hunting movements and by staring at it; their “fighting style” dictates something else.) We send the dog in both directions several times around the sheep, until it learns to keep its distance from them. This way the directions will be drilled into the dog. Then we can step back a little, leaving a larger distance but always only as far as the dog is still reliably controllable. Do not neglect to praise and to reward! When all this is accomplished in a stable fashion, we can increase the number of sheep and continue the distance exercise until the dog learns to stay farther away from the sheep. This is beneficial for a number of reasons: the dog always sees us and we see the dog and it’s less likely to nip than if we let it work too close to the sheep. Furthermore, the directions – independently from us - would be perfectly drilled into the dog; stopping the dog can be also practiced as part of this exercise, because we can stop the dog at will while it’s circling around. In addition, a new command can be introduced here, “go on”, which we use to encourage the dog to continue the circling or to further advance. This also comes handy, for example we stop the dog to slow it down, and we need to start it again, we will be able to send it on its way again with the “go on” command. With all these combinations we’ll be able to perform precise work!

With pen work or pushing through obstacles it’ll often sufficeto merely send the dog to a suitable spot and stop it, restart and stop it repeatedly. This will influence the sheep to “trickle” slowly into the obstacle. If we don’t slow down a volatile dog, some of the sheep will push through the obstacle, while the rest will escape bypassing the obstacle and running around it.

With pen work or pushing through obstacles it’ll often sufficeto merely send the dog to a suitable spot and stop it, restart and stop it repeatedly. This will influence the sheep to “trickle” slowly into the obstacle. If we don’t slow down a volatile dog, some of the sheep will push through the obstacle, while the rest will escape bypassing the obstacle and running around it.

During a typical task at trials, namely having to go around a post with the sheep, this is extremely useful if we really want to accomplish this in a spectacular manner. While staying in place, we send the dog a little ways ahead to one direction on the outside arc of the circle. As a result the sheep start gently to turn around the post. At this point we stop the dog and after a short pause we send it ahead again with the “go on” command. The dog will proceed to turn the sheep again a little. In order for the sheep not to turn too sharply into the post, we stop the dog again. We repeat this process until the sheep make a 360 degree circle around the given post or other object.

We can practice stops while sending in direction. When the dog stops, we send it ahead after a short while. If it doesn’t stop immediately, we have to repeat the command emphatically. We practice this until the dog stops. When the exercise is reliably successful at the distance of at least 15 -30 feet, only then we merit starting to work with sheep.

It’s important not to yell during any exercise, and not to let the dog feel that we’re nervous. If we make the dog understand from the beginning what is allowed and what is not, it’s more than sufficient to correct it emphatically, either verbally or by gestures – the dog will “get it”.

Gathering work

Gathering work can be achieved simply from the dog’s initial instinctive circling, i.e. that the dog stays on the opposite side of the flock from us and in essence, with our help, keeps the flock together, and will fetch it back later. As with each command, while teaching this, we need to move around a lot so that the dog understands better and faster what we expect of it.

We send out the dog in a direction. It’ll circle around the flock instinctively and should come back from the other side. If the dog keeps the necessary distance and we can slow it down on the opposite side of the flock – simultaneously stepping back, the sheep will start coming towards us. When the dog runs back to us on the opposite side, we send it back, assisted by swinging the arm, watching out for keeping a constant distance. The verbal command can be “get back”. If the cue by swinging the arm is insufficient, we can use a staff so that we tap the ground with it in front of the dog (do not tap on the dog!) on the side where the dog needs to turn. Alternately, we can simply hold out the staff in front of the dog as if we‘re blocking its way. This forces the dog to turn back; we do the same on the other side to turn it back again. At the same time we slowly walk backwards in front of the sheep, so they can move in that direction. The gathering work – “balancing” - develops later from this, as when we subsequently gradually increase the distance, fetching the flock will evolve.

We send out the dog in a direction. It’ll circle around the flock instinctively and should come back from the other side. If the dog keeps the necessary distance and we can slow it down on the opposite side of the flock – simultaneously stepping back, the sheep will start coming towards us. When the dog runs back to us on the opposite side, we send it back, assisted by swinging the arm, watching out for keeping a constant distance. The verbal command can be “get back”. If the cue by swinging the arm is insufficient, we can use a staff so that we tap the ground with it in front of the dog (do not tap on the dog!) on the side where the dog needs to turn. Alternately, we can simply hold out the staff in front of the dog as if we‘re blocking its way. This forces the dog to turn back; we do the same on the other side to turn it back again. At the same time we slowly walk backwards in front of the sheep, so they can move in that direction. The gathering work – “balancing” - develops later from this, as when we subsequently gradually increase the distance, fetching the flock will evolve.

When the dog understands that it has to stay on the opposite side of the flock, we can slowly start backing up in front of the sheep, keeping the dog continuously behind the sheep while helping the dog with commands and pointing. If any sheep separates from the flock, lags behind or tries to deviate from the desired direction, in the beginning we do not send the dog to it under any circumstances. We step out to help the dog and go for the sheep together, thus showing the dog what to do. We gently push the sheep back into the flock with the dog’s cooperation and continue to practice. Alternately, we can attempt to turn with the whole flock towards the escapee, and then to keep them together again.

When the dog understands that it has to stay on the opposite side of the flock, we can slowly start backing up in front of the sheep, keeping the dog continuously behind the sheep while helping the dog with commands and pointing. If any sheep separates from the flock, lags behind or tries to deviate from the desired direction, in the beginning we do not send the dog to it under any circumstances. We step out to help the dog and go for the sheep together, thus showing the dog what to do. We gently push the sheep back into the flock with the dog’s cooperation and continue to practice. Alternately, we can attempt to turn with the whole flock towards the escapee, and then to keep them together again.

While practicing this exercise, it can frequently happen that we can’t advance as fast as the dog is pushing the sheep, and they get ahead of us. In this case we stop the dog in the rear, the sheep slows down as a result and we start them again when we gain some space. Sometimes slowing down the dog will be enough. Another solution is if we step away from the advancing sheep and send the dog to turn the flock after us. We’ll gain some distance and as a result of the turns the dog will retain more effectively the idea of keeping the sheep together.

After some practice the dog retains that it should keep the flock together from the rear, thus it’ll be possible to turn and change direction in front of the sheep. As a result, after a while we’ll be capable of completing a more difficult course.

Stopping, turning back and holding the flock

When the dog runs by the flock to the front of the flock, curving into the front of the sheep, they turn around 180 degrees. If the dog stays there in the backside of the flock, wearing side to side – i.e. balances, the sheep will move back from the initial direction. Thus the balancing work is being established, which we can refine with holding in place, stopping and moving ahead again.

Stopping the flock is not a simple task and requires a lot of practice. The dog needs to know to stay or sit where and when it receives our command. Thus, if we send out the dog, it’ll proceed at a relaxed pace at the proper distance from the sheep, the sheep won’t scatter. This has been previously practiced with the dog. When the dog reaches the opposite side of the flock, we stop it immediately. The sheep will turn away from the dog, facing the direction of their escape. If the dog stays in place, the sheep won’t move, but as soon as we let the dog move slowly, the flock will move accordingly. This has to be done very gently, otherwise the sheep will get scared, may run away or the flock could scatter. To keep the sheep in place the handler’s help is also necessary. We also move calmly and slowly at a proper distance from the sheep, on the opposite side, possibly with arms spread, thereby we prevent the sheep from breaking out on the opposite side from the dog. The distance from the sheep always depends on the sheep’s tolerance towards the dog and humans. Naturally, less dog-broke sheep require a greater distance than sheep used to dogs. This is a difficult task with a Pumi.

Stopping the flock is not a simple task and requires a lot of practice. The dog needs to know to stay or sit where and when it receives our command. Thus, if we send out the dog, it’ll proceed at a relaxed pace at the proper distance from the sheep, the sheep won’t scatter. This has been previously practiced with the dog. When the dog reaches the opposite side of the flock, we stop it immediately. The sheep will turn away from the dog, facing the direction of their escape. If the dog stays in place, the sheep won’t move, but as soon as we let the dog move slowly, the flock will move accordingly. This has to be done very gently, otherwise the sheep will get scared, may run away or the flock could scatter. To keep the sheep in place the handler’s help is also necessary. We also move calmly and slowly at a proper distance from the sheep, on the opposite side, possibly with arms spread, thereby we prevent the sheep from breaking out on the opposite side from the dog. The distance from the sheep always depends on the sheep’s tolerance towards the dog and humans. Naturally, less dog-broke sheep require a greater distance than sheep used to dogs. This is a difficult task with a Pumi.

If we only want to turn the flock in a direction but we don’t want it to stop, we send the dog in direction already slowing it down, and before it’ll get in front of the sheep, we stop it or even recall it. This way, even though the sheep won’t stop, they won’t turn back and will turn in direction and continue ahead.

If we only want to turn the flock in a direction but we don’t want it to stop, we send the dog in direction already slowing it down, and before it’ll get in front of the sheep, we stop it or even recall it. This way, even though the sheep won’t stop, they won’t turn back and will turn in direction and continue ahead.

If we got to this point with our dog, we must practice these exercises, alternating them to maintain the dog’s knowledge acquired so far. If we neglect a task for a long time, it can happen that later we’ll have difficulties to accomplish it with the dog. What counts is not the distance, but to what extent does the dog “feel” the sheep, and to what degree can we accurately direct the dog. As long as keeping distance, stopping and staying are not 100%, increasing the distance is not advised because we’ll only be reinforcing the dog’s actual experience: specifically, that our “hands” don’t reach far enough. That’s why it’s necessary to drill into the dog certain basics, which, when already ingrained, will cause the dog to accomplish its assigned task reliably, even farther away from us.

Outrun, lifting, fetching

With sending in direction and distance keeping we virtually started the basics of the outrun and lifting; and with the balancing the basics of fetching the flock. This is gathering for all practical purposes, and with this knowledge the dog is capable of “holding” a flock, i.e. capable of preventing the sheep from running away.

(Video by: Magyar Zsuzsanna

featuring Menyhárt Krisztina and Vöröskői-Kondacsipkedő Borbolya "Porzsák")

At first we practice the outrun only from 15 - 30 feet; even if the dog would run out to 100 yards, it’s not going to be under control there, therefore we won’t be able to handle the dog properly. In other words, we won’t be able to help it if it faces an unexpected situation and falls apart.

We see such a loss of confidence, luckily, thanks to the dog’s little experience it recognizes the situation and finally corrects it:

(Video by: Magyar Zsuzsanna

featuring Menyhárt Krisztina and Vöröskői-Kondacsipkedő Borbolya "Porzsák")

In this case it’s also worthwhile to stick to the basic rule that we don’t increase the distance after the dog did the outrun to that distance once, but only when it completes the task at the given distance with full confidence. In other words, ingraining this in the dog is very important.)

In this case it’s also worthwhile to stick to the basic rule that we don’t increase the distance after the dog did the outrun to that distance once, but only when it completes the task at the given distance with full confidence. In other words, ingraining this in the dog is very important.)

We start the same way as earlier while training keeping the distance, namely when we send out the dog, we constantly “push it outwards” – but this time we don’t go all the way to the flock with the dog, but quickly step back to our starting point. We send the dog with the same command we trained it to gather. If the dog goes out in a nice arc, there is no need to “push it out”; we can confidently send it out from a stationary position. When the dog gets behind the sheep, we either slow it down or stop it. If the dog speeds up at the end of the outrun and cuts into the sheep, we could use a helper to stand near the sheep and to send the dog outwards in a wider arc; we have to be careful with that as most Pumik don’t appreciate this.

After slowing down or stopping the dog can start balancing immediately, and fetching the sheep at the same time. We praise it when it completed the task. If it completed the task successfully from one direction, we repeat it similarly from the other direction.

Classic gathering and fetching from a distance of 200 yards:

(Video by: Prépostfy Zsolt

featuring Menyhárt Krisztina and Vöröskői-Kondacsipkedő Borbolya "Porzsák")

Driving

We have nothing else to do, but to “whittle down” the gathering work acquired by now. It’s worthwhile to start teaching driving only when gathering is accomplished absolutely reliably. It’s useful to come up with a different command from the beginning. It starts with sending out but when the dog reaches the sheep, we stop it and send it in the opposite direction, so that the dog goes between us and the sheep. We let it move there while balancing and we only intervene if the dog passes the sheep or wants to push into their front. This will be difficult in the beginning as the dog would like to get in front of the sheep repeatedly and gather, but we don’t allow that this time. For that reason, if gathering is not ingrained in the dog deeply enough, the dog will get confused. It can happen that we send the dog to the front of the sheep, and when it gets there it stops on its own, having lost its confidence because it doesn’t know what we expect of it. If gathering is completely reliable, the dog will understand what we’re expecting of it relatively easily. We should use a completely different command, like “drive”. Here we also start out working closely and later on we can slowly increase the distance.

If gathering is reliable, as well as driving, the next step

If gathering is reliable, as well as driving, the next step

is switching between them. In other words, the dog should be able to switch from gathering to driving and vice versa at any given moment. We can start this by sending the dog for the flock 10-20 yards away, we have it fetch them and we call the dog to the front of the flock on the chosen side we point to. We stand in front of the flock to assist so the dog can see us, and then call it on the given side. When it got between the sheep and us, we simply issue the command “drive” and we start driving with the dog away from us. Gradually increasing the distance here as well, at first we only drive a few yards, then we command the dog to gather, to bring back the sheep. We switch between driving and gathering in this manner, and the dog should learn to switch in no time. Until this can be executed perfectly, we only move the flock away from us and back.

Switching between driving and gathering requires intense concentration, accurate work from the dog and experience in the basic tasks:

(Video by: Magyar Zsuzsanna

featuring Takács Ferenc and Vöröskői-Kondacsipkedő Futrinka "Fruti")

Later on, when the dog is working with the required precision, we can start the “oblique” driving. Imagine we’re standing at one of the angles. The dog has to drive the flock away from us, along one side. When the dog reaches the next angle, it has to turn the flock in the direction of the third angle, and drive the flock along the side of the triangle opposite us. This is the so-called oblique driving which is definitely difficult. Here the dog already has to be able to turn accurately and stop at the given instant – only then we can execute the oblique drive with it. This is difficult, because the dog will have the tendency to run out a little further as it already turned the sheep towards us; the dog could get into the gathering mode before the sheep will reach the third angle.

If the dog successfully reached the third angle of the triangle with the sheep, it’ll gather them and fetch them. At the conclusion of the sequence of tasks the dog will stop the sheep in front of us. We can practice virtually every task learned by now and switching between them with this sequence.

Other combined tasks

Penning and de-penning

Pen work is considered a more serious task as it requires great self-discipline from the dog, as well as complete familiarity with the tasks. The dog can’t be afraid of the sheep, not even when as a result of the sheep having been pushed into a corner, it’s forced into attacking the dog.

A nice solution for driving the sheep out of the pen is that we stand beside the open pen gate, we send in our dog, which deftly pushes out the sheep. Naturally, this sounds very simple, but in the real world there will always be problems. If the dog is high-spirited and overly eager – which frequently happens with the Pumi – it’s liable to barge in vehemently to the rear of the sheep and “blow” them out of the pen. Alternately it may charge the sheep and squeeze them even tighter against the pen fence. This is accident-prone for both the dog and the sheep; therefore in the beginning we should go into the pen with the dog to attempt to discipline it into self-moderation. This way we’ll be able to drive the sheep out nice and slow, and confident that the act won’t end with the sheep’s wild escape. After a few times we could even send in the dog by itself; and if necessary we chide it until it demonstrates calm and disciplined work.

A nice solution for driving the sheep out of the pen is that we stand beside the open pen gate, we send in our dog, which deftly pushes out the sheep. Naturally, this sounds very simple, but in the real world there will always be problems. If the dog is high-spirited and overly eager – which frequently happens with the Pumi – it’s liable to barge in vehemently to the rear of the sheep and “blow” them out of the pen. Alternately it may charge the sheep and squeeze them even tighter against the pen fence. This is accident-prone for both the dog and the sheep; therefore in the beginning we should go into the pen with the dog to attempt to discipline it into self-moderation. This way we’ll be able to drive the sheep out nice and slow, and confident that the act won’t end with the sheep’s wild escape. After a few times we could even send in the dog by itself; and if necessary we chide it until it demonstrates calm and disciplined work.

We have to be aware – especially with a young dog - that if it pushes the sheep into a corner, the sheep will be prone to charging the dog. A young, inexperienced dog will get scared if the sheep’s head turns towards it. We help the dog by turning the sheep’s head away from the dog.

If the dog is tougher, grippier, i.e.: more likely to nip the sheep’s feet

If the dog is tougher, grippier, i.e.: more likely to nip the sheep’s feet

when it has the opportunity, it’ll be more helpful to send the dog to circle around the outside of the pen, and to drive the sheep out by barking. In this case we can go with the dog, or we can be in the pen or by the gate according to our preference. If the flock is less used to dogs and people, it’s not productive to stand by the gate because the sheep wouldn’t even think of coming towards us. The best way to help the dog in this case is to stand beside the pen, leaving the gate open – as if to offer the stock an escape route. If the dog doesn’t have plenty of self-confidence and is a bit concerned with the stock, in the beginning we should definitely accompany it into the pen, even pull it by the collar and encourage it. While driving the stock out of the pen we have to be aware that if the sheep should sense that the dog is afraid, it can charge the dog and knock it down. This would tremendously set back our already insecure dog who as a result will be probably unwilling to go into the pen for a long time.

In penning we only have to watch out if the gate is relatively narrow, that the dog doesn’t push the stock too forcefully into the gate but it should let the sheep trickle in nicely. This way the dog is less likely to damage the stock. In most cases the sheep goes in willingly, knowing that it can expect safety and tranquility in there; this is the reason why it’s frequently sufficient to drive the sheep up to the gate and stop, sit or down the dog at a suitable distance. This is enough for the sheep to trickle in calmly on their own.

In penning we only have to watch out if the gate is relatively narrow, that the dog doesn’t push the stock too forcefully into the gate but it should let the sheep trickle in nicely. This way the dog is less likely to damage the stock. In most cases the sheep goes in willingly, knowing that it can expect safety and tranquility in there; this is the reason why it’s frequently sufficient to drive the sheep up to the gate and stop, sit or down the dog at a suitable distance. This is enough for the sheep to trickle in calmly on their own.

Getting the stock off the fence

It happens frequently that the flock gets completely “stuck” to the pen wall. In this case the dog has to squeeze itself between the sheep and the wall to peel them off.

Naturally, this is a difficult task for the dog as in many cases the dog is afraid of the danger of squeezing itself between the sheep’s feet.

Naturally, this is a difficult task for the dog as in many cases the dog is afraid of the danger of squeezing itself between the sheep’s feet.

For the first few times we have to hold on to the dog’s collar and keeping the dog closely next to us we push ourselves in between the sheep and the wall. At the same time we constantly encourage the dog and should it try to back out, we don’t allow it; we say the command:

“go back” or “back in there”. If we “stick” close to the wall, the sheep will instinctively start distancing themselves from it, slowly separating from the fence as they’re looking for an escape route.

When we completely “peeled” the flock off the wall, we immediately come back the same way, between the wall and the sheep; otherwise the sheep will stick to the wall again behind our backs.

At the same time, we say to the dog: “come here”.

After a few times we won’t need to pull the dog in between the sheep, it’ll go in on its own and then turn back right away. In many cases the pen fence or wall is not solid and the dog can go through it. This is very handy for peeling the sheep away from the fence as the dog is able to go through to the other side and bark at them.

After a few times we won’t need to pull the dog in between the sheep, it’ll go in on its own and then turn back right away. In many cases the pen fence or wall is not solid and the dog can go through it. This is very handy for peeling the sheep away from the fence as the dog is able to go through to the other side and bark at them.

Often the dog considers the passable fences as obstacles and it doesn’t go through them when it should. This can be taught by sending the dog to the outside. Using the command for sending out, we push the dog out through an opening it fits through for the dog to understand what we want of it and to make it believe it can fit through. It’s not rare that the dog is so surprised that it comes back in again, not understanding why it had to leave. When we push the dog out, we have to keep it out there, right next to the sheep and make it bark. After a few attempts it realizes on its own that the sheep can be made to move this way and this is in fact what we expect of it. When the sheep are slowly getting away from the side of the pen, we step in to prevent the sheep from clinging again and we call the dog back in.

We continue the herding work from there. Later on the dog discovers these options by itself and this is very helpful in getting the stock off the fence.

Splitting the flock

This task is not too difficult for the Pumi – its quick readiness for action, its courage and herding instinct dictate to position itself as close as possible to the stock; if necessary, it’s able to grip at any moment. During the first few times we should use a few – 8 or 10 sheep, so that when splitting and we go in between the sheep, it’s much easier to prevent the flock from closing up again behind us.

This task is not too difficult for the Pumi – its quick readiness for action, its courage and herding instinct dictate to position itself as close as possible to the stock; if necessary, it’s able to grip at any moment. During the first few times we should use a few – 8 or 10 sheep, so that when splitting and we go in between the sheep, it’s much easier to prevent the flock from closing up again behind us.

It may be practical to start the task near the fence by getting between the sheep and the fence. We call the dog, sit it or just stop it, then we walk in gently and part the sheep in front of it, we call the dog, possibly using the “come between” command. The fence behind our back can come handy to prevent the sheep from bunching up again. Naturally, the issue can be also resolved without the fence; in this case we just have to pay even more attention that the sheep don’t trickle back behind our back. This can be best prevented by moving between the two flocks, i.e. we drive one group of sheep away with the dog while we watch the other that they don’t join the flock being pushed away by the dog. The larger the distance between the two groups, the less the cohesion between them and less likely they’d run to join together.

It may be practical to start the task near the fence by getting between the sheep and the fence. We call the dog, sit it or just stop it, then we walk in gently and part the sheep in front of it, we call the dog, possibly using the “come between” command. The fence behind our back can come handy to prevent the sheep from bunching up again. Naturally, the issue can be also resolved without the fence; in this case we just have to pay even more attention that the sheep don’t trickle back behind our back. This can be best prevented by moving between the two flocks, i.e. we drive one group of sheep away with the dog while we watch the other that they don’t join the flock being pushed away by the dog. The larger the distance between the two groups, the less the cohesion between them and less likely they’d run to join together.

A more courageous dog won’t have any particular problems with this task; the dog will walk right into the midst of the sheep, next to our feet, without even giving it a second thought. If we’re working with a younger or more timid dog, it pays to reach over the sheep and to gently pull the dog by its collar into their midst. We also have to be moving back and forth at the same time to prevent the flock from closing up behind our or the dog’s back respectively.

When the flock is split, the dog has to be stopped immediately; otherwise the sheep could run and reunite farther away. Consequently the sheep will separate a few yards, and will keep that distance. Splitting the flock was successful! After a few times the dog will realize that it doesn’t have to be afraid of the sheep and what we really want it to do. Later on we can increase the number of sheep. If possible, we should practice this with sheep equally well accustomed to people and dogs and won’t run away wildly if we want to step in between them. It’s difficult even for an experienced dog to accomplish this task with untamed sheep. If we work with such sheep anyway, first of all we have to calm the animals by stopping them between the dog and the handler. This could take up to 20 or 30 minutes. If the sheep break out here and there, the dog can’t do anything else but constantly hold them back by balancing back and forth. While this is going on, it’s practically impossible for the dog to go in between the stock.

When the flock is split, the dog has to be stopped immediately; otherwise the sheep could run and reunite farther away. Consequently the sheep will separate a few yards, and will keep that distance. Splitting the flock was successful! After a few times the dog will realize that it doesn’t have to be afraid of the sheep and what we really want it to do. Later on we can increase the number of sheep. If possible, we should practice this with sheep equally well accustomed to people and dogs and won’t run away wildly if we want to step in between them. It’s difficult even for an experienced dog to accomplish this task with untamed sheep. If we work with such sheep anyway, first of all we have to calm the animals by stopping them between the dog and the handler. This could take up to 20 or 30 minutes. If the sheep break out here and there, the dog can’t do anything else but constantly hold them back by balancing back and forth. While this is going on, it’s practically impossible for the dog to go in between the stock.

Shedding a single sheep from the herd

If we have to shed one preselected sheep from the flock, we need a slightly different technique. This is really difficult and requires great concentration and cool-headed cooperation – and a tremendous amount of practice. The dog can’t make any mistakes here, otherwise the task fails immediately. The dog has to keep the flock together, preferably by sitting or staying but with the least amount of movement, so it won’t make the sheep too nervous. The owner cautiously approaches the sheep and steps in between the chosen sheep and the flock at a suitable moment, thus gently separating them. The owner recalls the dog to him. The dog has to move very cautiously and carefully, otherwise the sheep will run to rejoin the flock. If the work is done in a sufficiently calm manner, the sheep can be slowly pushed away from the flock.

“Here” and “There” commands

These are two well distinguishable sounding commands which differentiate between the near side – the side of the owner, and the “opposite side” – the other side of the flock. It doesn’t seem to be important to emphasize this at first hearing, however it’s essential to define to the dog somehow which side of the sheep it should work on.

For example, when splitting the flock, “get in here” is where we want to split it. Or if we want to turn away the sheep which is” stuck” to us, we point in front of us and tell the dog “here head it off”. We send the dog to the other side of the pen saying “walk in there”, or if it has to drive the flock towards us by itself on their opposite side, the command is” drive there”. It’s important that these two commands differ in sound, thus the dog can distinguish between close and distant work. We should use these and it’ll pay off. If we can distinguish between our hand signals as well, together with the verbal commands, it’s possible that we’ll be able to direct the dog in many different ways. For example, the equivalent of the “here” command could be raising our arm half-way up into the horizontal position, while the “there” signal could be raising the arm over our head. This can be seen at a distance, thus if we got the dog to pay attention to us while working at a distance from us, we can send it in the appropriate direction even without a sound. With this little supplemental element real professional work, herding from a stationary position could become a possibility, where the owner directs the dog while staying in place by a post, or from a starting circle. The dog then takes the flock through the course completely by itself, with the owner’s “remote control”.

Suggestions

If we drill these tasks thoroughly into our dog through various exercises, we can be sure that we’ll be able to perform excellent and spectacular herding work. Naturally, winning at a herding trial doesn’t only depend on this. It counts to what extent the sheep was dog-broke before the trial – especially as far as strange dogs are concerned. It counts how tired the sheep are - it happens that some beginner dogs are not even able to drive them out of the pen – they don’t move simply because they’re tired and a dog which is not forceful enough won’t move them. Trials also started after professional shepherds tried to dog-break sheep which never saw a dog before, for over two hours to make them willing to do something else, besides galloping away. Implicitly, it’s a difficult job to take such a recalcitrant flock through a trial course.

A difficult situation in most trials is that the neither the sheep nor dog is familiar with the site which can make them somewhat insecure: they’d react to things differently, slower or even more violently.

Another difficulty is that the sheep are not familiar with a given dog, they’re afraid of it and the dog is not familiar with the sheep used at the trial. If the sheep was never driven through the obstacles on the course before the trial, they’d be reluctant to bring themselves to go through the obstacles the first few times, because they are instinctively afraid of unfamiliar things.

One thing most people don’t think of initially is that it’s very important for the owner to be familiar with the sheep’s behavior; he/she should notice in time their intention to break out; should send out the dog in the right direction with the right timing and should stop the dog in time. Most often these are the reasons for the competitor’s loss. For example the owner sends the dog unnecessarily at the sheep which are nicely trickling through the obstacle, thus instead of all of them going through the obstacle they scatter and bypass it. The owner has to learn about herding at least as much as the dog – if not more.

We can also teach some of the commands and tasks without sheep. Possibly one of the most important ones is barking on command. The Pumi likes to bark, but it’s not too good if it continuously howls during herding. If we could make it bark on command – even from the distance – it’d be of great help. Often the barking is sufficient to warn the sheep that they’re being under supervision. Barking is indispensible for starting to move the flock. Warning from the distance is such an example, that is, we can practice anywhere with the dog the situation where it’s 15-20 yards away from us and we stop it in place, sit or down it. The Pumi has the tendency to grip or bite instead of barking, especially when the sheep is being recalcitrant – this is not desirable in trials, although we have to recognize that regretfully, often this is a necessary contingent for being able to take tired sheep through the course.

The owner has to learn to direct his/her dog which is controlled by instincts, has to be in tune with it; has to learn the sheep’s behavior in different situations, has to recognize particular situations as to what can be resolved, is it necessary to send out the dog at all, taking into consideration the condition of the sheep, has to learn to overview the individual tasks in 3 dimensions – for example: when does the flock need to turn to go clean around an obstacle. This sounds simple in writing, but actually it is at least as complex a problem as driving a car. As such, it can only be mastered by regular practice with sheep.

Frequent mistakes

Lack of verbal commands

It often happens with beginner or inexperienced dog owners that when they want to urge the dog to accomplish a task, they keep repeating the dog’s name more and more forcefully. The dog will know – sense that something is expected of it but in the absence of a command he tries various behaviors to attempt to satisfy its owner. Outwardly it’d seem as if the dog is unmanageable and distraught. However, the reason is only that the dog is seeking to fit in its own way because of its rule-seeking behavior. It is not always successful finding out what the owner wants from it. In this case I usually say: the dog already knows well what its name is, but unfortunately it doesn’t know what the owner is expecting of it…

Another characteristic mistake is that the owner sends out the dog with the command, but nothing else is communicated – it’s up to the dog what to do. The owner sees and senses that the exercise is not going well, but in the absence of experience he/she doesn’t say anything, doesn’t stop the dog if it carried out the command incorrectly. This kind of hesitant behavior can easily ingrain in the dog that it can do whatever it wants; the dog will make the decisions on its own and could override its owner’s command without any consequences, because the owner doesn’t make decisions in situations.

Confusing commands

Before starting an exercise it’s worthwhile to think over what we want and what commands we can achieve it with. It’s expedient to use simple, well-distinguishable words and completely unambiguous hand signals for training various tasks; thus the dog can easily glean from our words and body language what we want. Short, easy to say words can be easily remembered by the dog, as well as the owner. Thus it’ll become less likely to have a situation where we have to act quickly and in the big excitement the owner starts saying all kinds of different words, phrases and whole sentences to the dog because all of a sudden he/she can’t remember the required command. The dog certainly won’t be able to decide then what to do. Sentences made up of similar sounding but opposite commands are typical, such as: “Not that way! Away!” We should try to shout this to a friend from a distance; he/she won’t understand it at first, even though contrary to the dog he/she speaks the language. A nonverbal communication mistake related to this is that the owner points indiscriminately all over the place. For example if the owner sends the dog to the left, and points in the opposite direction with the right hand, the dog will get totally confused. The dog’s thought process is much simpler than ours and can be easily confused by crossing signals.

Quite often novice herding “wannabes” commit the mistake of trying to motivate the dog when sending it out, by shouting: “come, drive!” – it’s easy to see that we just cancelled one command with the other. The dog will rightfully ask as it hears the command: “What should I do now? Should I drive or should I come back to you?”

“Piling on” commands

Piling on commands happens when the handler feels that their dog is insecure in what’s expected of it. They try then to repeat the given command with a great frequency, in order to motivate the dog. This may be justified during the first few times of practicing a task, but when we see that the dog already understands what we want of it by the given command, we should gradually give fewer commands. On one hand, this way we’ll make our dog more self-confident and independent, on the other hand by not always reaching the dog with our voice, it learns to listen to us better. If we combine a command with a hand signal or some other movement, subsequently this will get ingrained in the dog; if it pays attention to us enough, it may be sufficient from a distance that we only have to repeat the movement and the dog will recognize the command. This is significant at a great distance or strong headwind. If the amount of commands is not decreased later, the dog doesn’t acquire independence in the course of training because it’ll get used to being directed at every moment; if it doesn’t hear the owner’s voice, the dog may block the command in unexpected situations or will become stubborn because it got used to not paying attention, after all the owner pays attention instead of the dog. If we issue commands less frequently, we cause the dog to get used to pay attention to us, or rather to “correct thinking”.

Right-left command (Click here to see the list of commonly used English herding commands)

I frequently hear during sending in direction handlers saying to the dog: right –or left! If one doesn’t signal the dog with hand signals or even by stepping out in the direction they meant, the dog will decide by itself which direction to go. If we repeat directional commands to a novice dog the many times, it’ll learn them. This command will work until the dog starts out from our feet and we assume that we never mix up the left direction with the right. As the majority of people will say right instead of left quite often even in this simple situation, I don’t recommend their use, although undoubtedly this technique works well with many. Furthermore, if the dog goes to the front of the sheep, i.e. the opposite side of the flock relative to us - its task is to fetch the flock to our front – we’ll have to concentrate what we tell it. In most cases, the dog won’t even hear from 200 yards whether we shouted left or right.

If, however, we teach the dog hand signals and stepping out, we achieve two things simultaneously: it’ll work accurately even from 200 yards, and we force it to pay attention to us, and not only when we’re yelling! With a little practice the dog will run behind the flock and will peek from the side from time to time to see what we want from it – in other words we forced the dog to maintain contact.

Fighting with the sheep

It’ll happen occasionally that a more aggressive ram

It’ll happen occasionally that a more aggressive ram

will turn on the dog and will fight with it. If the dog replies in kind and the ram doesn’t head back into the flock, the dog will “turn on” even more and will fight with the ram more aggressively. The ram won’t even think of returning to the flock as long as its being attacked, because its instincts dictate “do not turn your back, do not render yourself defenseless to the attacker!” In the meantime, the flock quietly walks away.

We have to stop immediately and call it off the courageous ram, as the ram will return to the flock, and we lead the dog to the conclusion that if it moves away from the aggressive ram, sooner or later that’ll escape back to the flock – and at the same time the dog doesn’t lose sight of the flock. We call this movement “moving out”.

If we drill this into the dog with the necessary frequency, with time it’ll gain such experience that we can safely leave it with a whole flock and it’ll bring them back without any losses.

Crossing or losing direction

While sending in direction, a frequent error is that the dog crosses, i.e. as it gets to the flock, it doesn’t go around the flock at the direction it was sent, but in the opposite direction, and the owner lets that happen without a word. If we don’t correct this in a timely fashion, it’d be even possible that the dog will be willing to go around the flock always from one direction. This is a big mistake, because by doing this the dog will force the sheep, which is already moving in the wrong direction, to head even more in the wrong direction.

We have to act as we catch the dog in the act; that is, as soon as we see that the dog is starting to veer towards the wrong side as it’s running towards the flock, we immediately stop it and we convince it to head in the correct direction by emphatic gestures, hand signals, stepping out, or possibly – if the dog refuses to understand – by running in the right direction. If it really doesn’t get it, it’s best if we recall it and start it again. If the correction was successful, we praise the dog profusely. Afterwards we repeat the same direction 3 or 4 times, until it understands what we expect of it. If the dog understood this, we start with the other direction immediately, so the dog will understand the difference between the two directions.

We repeat this chain of exercises from time to time, after other exercises, so the satisfactory execution of this task will be sufficiently ingrained in the dog. If this isn’t going too well, we get closer to the flock and we send the dog from there again. We only increase the distance when the dog executes the exercise reliably from the given distance.

If he ever comes back..!

A typical novice handler’s error is when the dog leaves, and doesn’t feel like obeying; the owner is angry because he lost his control over the dog. He recalls the dog with great difficulty – who runs back happily after the mischief. When he gets back, the owner severely chastises, or even hits him. From this chain of events the dog develops an instinctive defensive mode – he quickly realizes that if he doesn’t come back, the owner can’t chide him. The dog’s thought process is different from that of a human’s: it’s simpler. It’s not capable of far-reaching conclusions, things get ingrained in its brain simply by experiencing. Hence, we can do two things in this case: either we go after the dog and we settle the account where it committed the mischief, or if it already came back, we shouldn’t chastise it under any circumstances. Thus next time we can count on it that it’ll come back.

It happens sometimes, that the dog is so much aware of the fact that it is the leader, that is, when the owner goes after the dog after an unsuccessful recall, the dog runs away from him. This develops into a frolicking chase around the sheep, which the dog enjoys and may perceive this as a reward. This positive experience quickly fixates itself in the dog, who can’t even imagine a game better than the chase!

It’s not a solution if helpers chase the dog away from the flock towards the owner, because mistrust could develop in the dog towards strangers; subsequently, it may not work properly if anyone is on the course – even a judge at a trial. It may also happen that the dog will pay more attention to the helpers because it’ll respect them instead of the owner. This is not a goal either, because the dog has to work with the owner and nobody else.

There is only one way out of this situation: if the owner and the dog settle the social order between themselves and build a harmonious relationship based on trust. This, in turn, is a longer process, but unfortunately, in the absence of this, any advance in herding is not to be expected.

Laxity

It’s probably the most common occurrence among dog owners nowadays, that they treat the dog as a member of the family; this means to them that they do not command the dog, they ask the dog. Well, this can work harmoniously in a family setting; however, the behavior of a dog with good herding instinct will change to the extreme around sheep. The balance of power will change, as the dog will find itself in an environment where all of a sudden he is the boss and can rule over the stock at will. If the owner is not forceful enough and lets the dog take the lead completely, the otherwise well-mannered little pet may turn at once into a disobedient little devil. This is undesirable around livestock and will cause elimination at a trial. Therefore, the owner has to learn that the emotional world of the dog is working by different standards; accordingly, if in a given situation the owner firmly yells at his dog, the dog won’t collapse emotionally but will grasp the legitimate circumstances and will become aware of the fact that in reality, he is not the leader…

Laxity is a disadvantage not only with confident, headstrong dogs, but with insecure ones as well. If the dog is not brave enough and doesn’t dare get near the stock, we can support it in its action with firm, decisive presence. When the dog sees that this results in success, it’ll be easily encouraged. The reason for this phenomenon is that the dogs’ social structure is hierarchic, and not equal in social relationships as that of humans. If we don’t build up this hierarchy with the dog, i.e. we are not its superiors, then the dog will instinctively create it so, that most frequently it is on top.

Running

When we teach the dog, we frequently have to run with it in order to emphasize the command. Thus the dog will find out quickly what we want, from the chain of actions. It can happen with a less motivated dog that we must run later as well, because the dog will be more attracted to a smell at the moment – or it’s bored with the whole thing already – rather than to start executing a command. In this case the owner will instinctively start running in order to prevent the sheep’s movement in the wrong direction. This will cause the sheep to run even faster, together with the dog. The result with a less experienced dog is, that the flock of sheep will run away and off the course. It’s not a pretty sight to run through the course this way, it’s impossible to go through the narrower obstacles running; we also have to realize that the sheep are faster than us… The goal is not for us to herd, but for the dog to work.

If we sufficiently slow down, the sheep will slow down after a little while and stop.